Writing Styles: Exiled, Outsider, Obsessive

An unusual post: obsessive and taking a peculiar course, winding together my wrestle with a mild-ish case of OCD with the political exiles of writer Ariel Dorfman and the effect of an outsider point-of-view on writing styles. Yes, definitely odd.

Under the title “Letter to an Exile,” it won first this year in the Intercultural Essay category of the Soul Making Keats Literary Competition. I was quite drawn to the name of this contest, which refers to Keats saying that life is not a vale of tears but “a place of soul-making.”

The piece, in the form of the letter, was written years ago, the part about Dorfman appeared in Durham’s INDY WEEK. Here’s the whole long self-revelatory (perhaps self-indulgent story) Letter to an Exile:

Dear Ariel Dorfman,

I’m the one who asked you the irritating question from the audience at your reading Thursday night at The Regulator bookstore in Durham, NC.

I wanted to write you a note—I’m not sure I ever made clear what I was asking. It had simply occurred to me, as I sat among your twenty-or-so listeners in the store’s basement, that in your novel THE NANNY AND THE ICEBERG your voice differs from writing styles of most novelists at work now in the United States.

You give such liberty to the narrator, for one thing, to discuss the story as it unfolds. What interested me, though, was not how your writing is different, but whether you have an awareness of being set apart. And is your “different” voice a choice? And what has it cost you?

I did know that your first language is Spanish, and that you’d been deported years ago from Chile; so without considering my choice of words, I asked if you knew what it was in your style that made you different from American novelists.

Immediately, I saw I’d asked an offensive question. You are an American novelist, you said—Latin American, for a start. Plus, of course, you’ve lived in the U.S. for what is it now…thirty-some years? “I’m for the mongrelization of everything,” you said, arguing for a true melting pot of national identity.

Okay—point taken, I should have said United States. And it’s true: I would have done well to have already read your memoir HEADING SOUTH, LOOKING NORTH: A BILINGUAL JOURNEY. But I wonder: if I had asked my question in acceptable language, and had done the proper advance research, known how many times you’ve been uprooted from a language and a life, would you have answered my question? Would you consider the possibility that your voice is different from the mainstream? Would difference be admissible or acceptable?

This note is starting to expand beyond my intention, but I want to tell you what unfolded three days after that evening. It was, by chance, the Fourth of July, and I lay propped in bed at home reading your memoir, which you’d inscribed with an amiable testiness, “how to be another sort of ‘American.’” At mid-morning, the heat index outside had risen to 105 degrees, and my husband Bob and I were celebrating victory in the American Revolution by lounging in the air-conditioning with books.

I kept interrupting Bob’s reading to offer him tidbits from your story: persecution driving your Jewish parents out of Eastern Europe to Argentina, forcing you out of that country when your father spoke against the right-wing military government, the McCarthy hearings then running the family out of the U.S. to Chile (by then you’re thirteen years old), your own exile from your chosen homeland of Chile with the fall of your Marxist president Salvador Allende. The threat of death, torture, another uprooting: all too familiar. “He didn’t start off as Ariel,” I told Bob. “His name was Vladimiro.”“Why are you so fascinated by this guy,” Bob said, putting his book down. A clinical psychologist, he was reading some new research on marital therapy.

“I’m not.”

“You went to hear him.”

“Laurel and a couple of other buddies were wanting to go….Actually he kind of irritates me.”

Silence.

“It’s because what I’m writing about is so much like his life—somebody who becomes an outcast in her own country and then leaves, only to have a similar sort of violent politics break out again years later in the new place.”

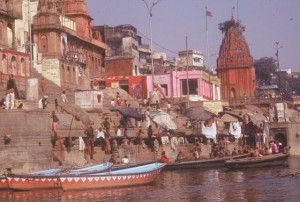

From Bob, a skeptical sound. But that had been a pretty good answer, I thought, true and close to the bone, though, for me the persistent image was not so much of being uprooted, but of someone on the run and having to face again at each new place, at every turn, the same crisis…no escape. I’d been working, intermittently, on my novel, “Sister India”, set in India and the southern U.S., for eight years.

A moment passed. “And I’ve wondered,” I said, “I’ve thought about it: if I could hold up, or if I’d recant, give myself up, under torture.”

The off-duty therapist half listening on the other side of the bed said: Aha, that sounds more like it’s leading somewhere. Pushing the covers off his legs, he sat up, back turned, feet on the floor. “You would,” he said. “Hold up.”

“I don’t think so. I don’t know.”

Bob started to get dressed—enough, apparently, of this conversation for him. I went back to my book, reading how you, Ariel Dorfman, once escaped being tortured to death only by a fluke change in your schedule. I am with you as it happens, in the final hours of Allende’s Chilean Revolution. A colleague, an old school friend, has swapped shifts with you, keeping watch and manning the phone at La Moneda, Chile’s Presidential Palace, with its four-foot-thick walls, where you’d been working as a cultural and media advisor.

On this night you are at home, putting your young son Rodrigo to bed. Then comes the phone call: General Augusto Pinochet’s take-over of the nation has begun. It will be your friend instead of you who dies.

A shocking twist of luck—anyone would feel some guilt, if that’s the right word. In any case, you’ve turned the events of that night over and over in your mind in the years since, imagining your friend tied naked to a chair as a man in uniform approaches with electrodes, a long needle—

My torture question is a way to test myself, I think, as I linger on the waterbed with a book, taking a restful holiday in honor of the bloody revolution to which I’m indebted for independence.

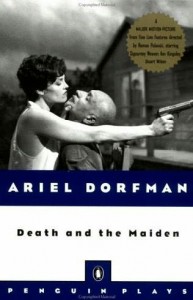

I did see the movie made of your play DEATH AND THE MAIDEN, Ben Kingsley playing the torturer. The scene I can’t forget is the glimpse of him seated in the box at the opera with his family, looking normal and ordinary. And the question that the story asks: will the nonviolent victim of horrific torture perform the same acts on her captor when she is given the chance? Or will she hold her ground?

Maybe my own question—I have to go on with this, please bear with me—maybe it is one of the ones everyone asks of themselves: Do I have the guts? Will I hold on that powerfully to the loyalties, the values, the voice that is mine? Is my love for anyone or anything that strong?

I have wondered too if at the heart of the matter for me are my memories of segregation and the fact that, as a white kid, I managed to live it without seeing it or doing anything to change it. In those years, different voices were urgently needed, and the difference would have been far more than a matter of style.

But perhaps the reason I’m reading this personal history of yours so avidly is simply that I sense in you tendencies that are also mine and that I fight indulging—near-manic enthusiasm and outrage, for example, sometimes displayed in a righteous and grandstanding way. In your book, you give a portrait of yourself as a young political activist: “I was everywhere, vociferous, exhorting, convincing, boundless in my energy and my convictions.” Exuberance, you call it, even exhibitionism.

Do you happen to recall the one other time you and I crossed paths? It was many years ago, in the first days of the death threat against Salman Rushdie when his new novel had given offense to Muslims. I remember the night well, because it was snowing—so unusual here—and the streets were iced, the town shut down. The reading, at Southern Sisters, feminist bookstore now long closed, was held in spite of the weather and people did straggle in, enough to fill the room. You and I and other writers were to read aloud from Rushdie’s book, to support his freedom of speech, to protest the threat to his life. I prefaced my own reading with a few mild comments that amounted to “gee whiz, how awful—being from Eastern North Carolina, I can’t imagine having to worry about people trying to kill me over what I write.”

Novelist Clyde Edgerton read next, and I immediately recalled, though he did not mention it, that here in this same Eastern North Carolina his university teaching contract had been called into question after his first novel stirred religious controversy and he’d wound up resigning.

When it was your turn, Ariel—and this more than the snow is likely the reason I so clearly remember the occasion—you seized the podium, bristling with energy and importance, on that too-quiet night when cars didn’t even pass outside, and announced: “I have spoken this morning with Salman. He is well and thanks you for your concern.” I rolled my eyes; so theatrical, I said to myself, and what a piece of name-dropping. You proceeded to read a passage from Rushdie, marbled with foreign phrases, which you pronounced correctly and with relish. I disapproved of your lordly air as you showed how at home you were in all those languages, resented how resoundingly at home with yourself you seemed as you stood there.

I did not then know that all of your life has been a struggle to find a safe home, and a language you would not have to leave, how you have been divided in half, torn even in your own mind: to live and think in Spanish, or in English…. “Wasn’t I, in effect, a foreigner?” you write of your life in Chile. “And wasn’t I destined to be one forever?”

Closing your book, I got out of bed, marking my place a third of the way through. Bob and I drove the half hour from where we live out in the country into Chapel Hill, to get some exercise: he swam, I lifted weights and sauntered a couple of miles on the stair-machine. It was later in the afternoon, when, freshly showered, browsing through a video bar, I felt myself sink down through those earlier answers, about distinctiveness and exile, to another thought. On the cover of a video case, a blurb praised the movie Cousin Bobby as a “lovely evocation” of the personal sources of political conviction. To me that meant: how we each come to our particular voices and stances.

Your story, Ariel, shows so clearly the roots of your own conviction. Your parents were Communists; you grew up wanting to help the masses, though you hadn’t met them. The repeated flights and deportations had their own effect: “…it was that persistent hunger for a real community that had now led me here, to this revolution, to this place in history.” You were lucky in the fall of that government not to be executed, and that has charged you with a duty to tell the world about torture and injustice. As you describe it, you have been “keeping a promise to the dead.”

My life, my luck have been so different.

I grew up in the 1950s in a North Carolina beach town, Wilmington, with the ocean only minutes from my house. I was as rooted in that town as the oaks and magnolias I loved to climb, and that I can still, forty and more years later, remember so exactly, knowing where to put a foot and then a hand, the knobs and hollows in the trunks that made good “holds.”

My parents, who loved me, owned successful clothing stores that carried our last name—Payne’s—written large and green, with lights behind the letters, across the front. My parents’ place in the community gave me not just affluence but social status, a guaranteed summer job (until I was able to get the local newspaper to hire me) and clothes—once, I recall, a dress that was on the cover of that month’s Seventeen. In a town and a time where privilege belonged exclusively to white people, I was as pale, nearly, as notebook paper. And when it was time for college, I went to Duke University, where you now teach. On the whole, I’ve been lucky in my adult life as well.

My own establishment-liberal politics did not begin as politics, but instead as manners. Working at my parents’ clothing business as a teenage clerk—handing, face averted, a larger-sized bathing suit into a dressing room, pinning the hems of men’s pants for alteration—I was told to treat every person, at the store and elsewhere, with respect and also with care for their touchy pride. One morning, as we rode to work, my father offered a bit of advice: don’t ever say to a customer that the size or shape of any part of their bodies is unusual, “even if you think it’s a compliment.” If it stands out, he said, it’s something they likely feel sensitive about.

And so, decades later, against that counsel, I dared to suggest that your writing voice is unusual, stands out. I did not know how earnestly and painfully you have remade yourself time after time.

I do know something, however, of what it is to mold one’s persona, to tailor oneself to the shape that the world seems to want. It’s a long story, but not the digression it may first seem; here’s the pivotal moment: it was a summer afternoon in 1956, when I was between second and third grade. I was sitting on the back porch staring out across the azaleas to where the sun came down hard on the grass. I was an odd child, mostly happy but prone to sudden fits of crying that no one could understand. At this particular moment, I was in good spirits. Mom, still in her work-at-the-store high heels, straight skirt, was sitting with me, flipping through a magazine, as we talked and I drifted in and out of a good-humored reverie. I ventured aloud that maybe I might like to join the Brownie Scouts.

Mom’s question to me: would Brownies become another reason for a crying jag?

I snapped to alert attention, taking this in, its implications. I was startled by her question. I was fine, had always been, would always be. Yet I knew what she was talking about; it was embarrassing to even turn over in my mind. I feared that just by thinking of one of those episodes, I might engulf myself again in that same state, unstoppable once it began: at such times, I’d recognize that something I’d said or done was bad—on one occasion I’d looked at “dirty” pictures, stared at them, people in flimsy underwear in a catalogue. Then the certainty would flood toward me that it was worse than bad: it was evil, I was now evil, facing only shame for the rest of my life, wherever I went. In exile everywhere. I would fall into the long wordless fit of sobbing; afterwards the rest of the day I’d feel weak and sick. Days or weeks later, it might be some other sin I had committed.

But this afternoon I was feeling good. Bad days were not something I wanted to talk about. I surely wasn’t going to let any of that stop me from joining the Brownies.

Sitting there on the porch, I made a decision. I took control of myself; I assumed an appearance of ease. I never again burst into tears at school. I went on to become a Girl Scout, a girlfriend, a news reporter, a travel writer, a wife, a novelist.

Once I’d stopped crying—and lots of young children cry—I felt reassured that I was pretty much the same as everyone else. Because, over the years, the bouts of piercing guilt did diminish, smoothing out, mostly, to a constant background whisper to be careful, do nothing wrong. I had no reason to think that this wasn’t how all people lived: I understood that everyone worried, and I thought by then that that was all I was doing. The reason other people were not so tense and hesitant as me was surely because they were better at hiding worry than I was.

As I start to remember this, more details come back: my counting and recounting squares on the Monopoly board, to be sure I didn’t move my “man” the wrong number, thus cheating other players. I know that I embraced the classic injunction to doctors: First, do no harm.

And of course I was praised for being such a good girl. One teacher told my parents that she’d never seen a child my age with such a highly-developed conscience. When anything broke—the motor on my family’s outboard boat—I knew it was my fault, the queasy certainty of wrongdoing rushing through me once again.

“You could view that as grandiose,” my husband says now. I’d believed I had the power to break a boat motor when I wasn’t even driving; I’d merely leaned my weight against that motor earlier in the day.

Only once do I remember questioning whether this kind of thinking might be crazy, whether I might be far more separate and different that I’d want to claim. Doing my homework, in fourth or fifth grade, I had just thrown away, sheet by sheet, a great pile of clean paper because I had touched and possibly contaminated those particular pages with germs on my fingers from my mouth, nose, eyes.

I was calmly sure of this, though I knew I hadn’t touched the paper differently than at any other time. But there lay that stack of wasted paper: bright, white proof of something odd. I flopped down on my bed and started making up a poem about my efforts to be sane, then told myself, with detached amusement: don’t be melodramatic, you don’t know what it is to be really crazy.

As an adult, I believed for decades that all such troubles were behind me. Or, at least they were reduced to a state of hyper-conscientiousness, over-responsibility for everything that involved me, which could pass as a virtue.

It was a winter when I was in my late forties that my fevers of guilt began to come on again.

Their reappearance coincided with the dropping of my estrogen as I approached menopause, perhaps returning me to a chemical state not unlike that in my childhood. Two or three episodes occurred, during a period when I was frantically busy trying to finish a nonfiction book for a women’s clothing company, Doncaster: a book, as it happens, on the expression of one’s true personal style. Each of those rounds had caused me to lose, for a day or two, my focus on what I was writing. In one instance, I was fearful and grief-stricken that I might not have paid enough county taxes, because I’d resolved one gray-area question in my favor rather than in the county’s, and that the shame of this would circuitously come to damage my young nephews and ruin their lives. When that bout had passed, I looked at my schedule: I was six weeks from my deadline, with so much still to write that I could not afford to lose an hour. So, I made an appointment with the psychiatrist I’ve seen on average about once a year over the past thirty-five years. For the first time, I described in cool detail one of these episodes that had been absent from my life for so long. I didn’t even need to finish my story; my doctor recognized it at once. He gave me a sample packet of pills. I swallowed one, and came home for the first time to free and clear possession of my own mind.

So, I was forty-eight years old before I discovered that my lifelong habit of obsessive guilt and checking and counting, the whisper to be careful and not say the wrong thing, was obsessive-compulsive disorder.

I had not recognized it because, for me, it is almost entirely internal: my chemistry had never driven me to mad handwashing, the best-known symptoms of OCD. Yet it has tainted all of my thinking and formed the larger part of all that I have ever thought: Did I say the wrong thing? Should I not have done that? If I leave this lying here, might it fall and break someone’s neck, paralyzing them, changing lives, mine included, forevermore?

Not until my obsessiveness was nearly erased by medication, did I have more than a hint of its dimensions.

Ariel, I must tell you: this is not what I meant to write at all. I meant to defend my question, as reasonable, to say that it’s not bad to be unusual, even perhaps to assert some kinship in “differentness.” I’d far rather read a distinct, authentic voice than one that “fits in.” Wouldn’t anyone?

But it’s so difficult, I know, to risk losing your place in the world by seeming “the odd man out.” I picture you, tall and blonde and fair-skinned, in Santiago bent on being fully Chilean. I was bent on being normal, or at least seeming so.

My voice—thinking, speaking, and writing—is now largely free at its source from the worst of obsession, moral nit-picking, and guilty imagining, though I know that that lies low-level in the background undistinguishable because it’s so familiar. I take a modest few milligrams of an anti-anxiety drug every day, currently fluvoxamine. For its liberation of my spirit, I am grateful.

Since beginning that regime, my writing has been so much easier. Walking down the street has been easier. Talking to people is like letting water pour. I do continue to think twice about a lot of things—as this letter amply demonstrates—but my conscience is no longer a full-time capricious tyrant, no Pinochet. I discover over and over in my new freedom that life is vivid and delicious. In all those years, I had not known that, as your Chilean poet Pablo Neruda wrote: “desterrado del esplendor de las naranjas.” I’d live exiled from the shine of the oranges, lived in fact with my own light clouded.

Now I’ve put all this on paper and I’m startled to have done it, though not displeased— But back to where I began: having, for better or worse, a different voice. The distinct quality that I noted again in the piece you read at the bookstore was the way your narrator comments and rhapsodizes, moves easily through time and space; whereas, it’s more fashionable in North American fiction to plunk the reader down into a scene, with all its particular sensations, and let the narrator evaporate as the scene realistically unfolds.I could well understand if you didn’t want to evaporate.

Probably the personal sources of political conviction are no more than a threat—either in one’s nature or from the outside world—to one’s sense of having a solid place in the world. If you’re a serious kid, and one guided toward altruism—then you find yourself beginning to form plans for how the world ought to be governed and how not only you, but all people can fare better.

In my world plan, I like to imagine a system that allows everyone to speak their boldest, weirdest, most original thoughts without any cost, without any risk at all—no exile, no violence, no loss of livelihood or respect or credibility or love. Of course that will never happen, though it can be arranged in private, person to person, which is perhaps why much of your memoir of language and identity is about your alliance with your Angelica and this letter of mine hatched out of a reading-in-bed conversation with Bob.

I’ve come now in your memoir—in this binge of alternately reading it and writing this—to an admission from you that jolts me. Page 246: “Ever since I could remember…a vague heartache of guilt had been gnawing away at me, dripping into me like a deformed twin who whispered that I was to blame, always to blame for whatever was wrong, that I could never do enough to make things right.” So—perhaps it was this I sensed from the start, making me want to draw back that night at Southern Sisters: that it seems we share a profound and burdensome difference.

One more thing—I asked about your writing styles as if I’d expected an answer. In retrospect, I don’t think I did. I wanted to make contact—and of course to get attention. Mainly I wanted to talk about voices, because to do so is a way of running my fingers once again over the fabric of language, trying to soak in a sense of its structure, mainly for the sheer delight of it, but also to understand precisely how language, which can cloak—how well I know!—yet can also accomplish the most radiant, even flamboyant, self-expression, which, now that I am more at ease in the world, I both allow and pursue.

Almost every day of my life now, I revel in my still-new discovery that I am more than simply at ease. Indeed, I am at home. And you are one who can understand what that means.

You may understand this as well: I’m not going to close this letter-turned-essay with a summary of my conclusions. I’ve done that many hundreds of times in more than thirty years as a freelancer, written a tidy summing-up, in the process reducing material with the potential for mystery and “juice” to its dry bones. What I’d rather do now—and this is my neglected deep longing as a writer—is to allow my meandering journey of discovery to touch you or any other reader in whatever way it will, as bits of your memoir have stirred me. I want some bit of my story to play the part of a madeleine, opening or re-opening a door in a reader’s life.

I’ve gradually come to realize over the last couple of years that I have no alternative to writing as I do now; I can no longer put on a voice that doesn’t suit me.

The process of writing in a more authentic and meandering way has seduced me. My mouth actually waters at the prospect of mulling, hour by hour, over prose that trails, like yards of silk, unshaped into any obviously serviceable article, yet so rich in itself, and various, depending on movement and how the light falls. Music works that way, its meaning evoked through pure sensation that leads to emotion. Fiction unfolds in a similar manner.

And your own story, with its passions, its structure, its diction, its rhetorical excesses, its plain facts, all so distinctly yours—yet my reading of it opened a corridor for me that tunneled deep into my past and, as I let my thoughts unwind here, has begun to travel with me forward as well, toward possibilities in my future, as I become, for better or worse, “another sort of writer,” if not, as you said, another sort of American.

So, Ariel, I thank you for this conversation. My congratulations to you, both on the peace you’ve made between your Spanish and your English, and on your own stories. Que le vaya bien. I wish you well.

Sincerely,

Peggy Payne

Update: Ariel Dorfman on receiving this letter wrote me an admirably gracious reply. His latest book is, fittingly, FEEDING ON DREAMS: CONFESSIONS OF AN UNREPENTANT EXILE

My SISTER INDIA was published two years after this was written and chosen as a NEW YORK TIMES Notable Book of the Year.

Categories: Uncategorized

Tags: a, Ariel Dorfman, authentic, c, checking and counting, Clyde Edgerton, communists, contaminated, Death and the Maiden, deported, Doncaster, Duke University, exiled, fluvoxamine, foreigner, guilt, highly developed conscience, hile, La Moneda, llende, McCarthy hearings, medication, obsessive guilt, obsessive-compulsive disorder, ocd, outcast, outsider. obsessive, Pinochet, point-of-view, Salman Rushdie, say the wrong thing, soul making Keats, symptoms of ocd, torture, wrongdoing

Comments

I think I must obtain and read some of his (Dorfman’s) books immediately. If they evoked this kind of response from you – they must be worth checking out.

I’ll be interested to hear your response, kenju. My response to that first memoir took me on quite a trip.

Born in 1944. Reflection of my childhood experience (and as a male in NC).

Reading this, yet again – happening …

prone to sudden fits of crying that (almost) no one could understand. – See more at: https://www.peggypayne.com/writing-styles-exiled-outsider-obsessive/#sthash.z0muohY4.dpuf

Sympathy, Robert Braxton!